Over the past 10 years, “user experience” (UX) has been the subject of a lot of discussion. And there are lots of definitions. Here are 40 of them: https://www.allaboutux.org/ux-definitions.

I really have no objection to any of these definitions — apart from the fact that they fail to suggest any relevant course of action. Our industry tends to preach to the choir, but neither to the client nor the bank. We invent new buzzwords (old wine in new bottles) and hold expensive workshops (lots of stickies on the wall, but usually without long-term benefits — call it “UX Theater”).

Over the years, I have spoken to hundreds of business leaders who all tell me more-or-less the same thing: “Yeah. Happy customers buy more. But what are you going to DO?” So, I tell them. And now I’m sharing this with you, too.

UX = the sum of a series of interactions

User experience (UX) represents the perception left in someone’s mind following a series of interactions between people, devices, and events — or any combination thereof. “Series” is the operative word.

Some interactions are active — clicking a button on a website, giving a server your order at a restaurant, getting out of the rain at a picnic.

Some interactions are passive — viewing a beautiful sunset will trigger the limbic system to release dopamine (a reward chemical). This applies to any and all of our five senses.

Some interactions are secondary to the ultimate experience — the food tastes good because the chef chose quality ingredients and prepared them well. The ingredients are good quality because the farmer tended his fields. The crop interacted well with the rain that year.

All interactions are open to subjective interpretation — some people don’t like celery or sunsets. Remember, a perception is always true in the mind of the perceiver; if you think sunsets are depressing, there’s little I can say or do to convince you otherwise. However, this is why designers often fall back on “best practice” — most people react favorably to sunsets.

It’s also important that you take a broad view of UX. This is not something that just happens on a screen. Perhaps this is why the pixel pushers get so frantic when other communities start to talk about service design and non-digital experiences. But more about that later.

UX design = combining four types of activities

Designing a “user experience” represents the conscious act of:

- Coordinating interactions that are controllable (choosing food ingredients, training waiters, designing and programming buttons)

- Acknowledging interactions that are beyond our control (uncomfortable seats in a 100-year-old theater, lack of fresh produce in winter, low-hanging clouds that hide a sunset.)

- Reducing negative interactions (providing tents as emergency shelters at outdoor events in case of rain; making sure restaurant seating next to the noisy kitchen door is the last to be filled, putting in an extra intermission so folks can stretch their legs).

- Examining the journey between interactions (we’ve all experienced filling in a form somewhere that suddenly asks for documentation we don’t have close at hand — a passport number, a car-registration document, a driver’s license number, etc. By the time we find the papers we need, we are often timed out and must start all over again.)

A good user-experience designer needs to be able to see both the forest and the trees. That’s because user experience has implications that go far beyond basic usability, visual design, and physical affordances. As UX designers, we orchestrate a complex series of interactions. Here at my company, we call this “The CARE Model” because Coordinating, Acknowledging, Reducing, and Examining form a convenient acronym.

The “blueprint”

The first step is to identify the relevant interactions and arrange these in some kind of (usually) linear order. There are any number of remarkably similar models for doing this: “Touchpoint Analyses,” “Customer-journey Maps,” and “Service-design Blueprints” immediately come to mind. Common to all of these is that you WILL be putting stickies on the wall and rearranging these at regular intervals.

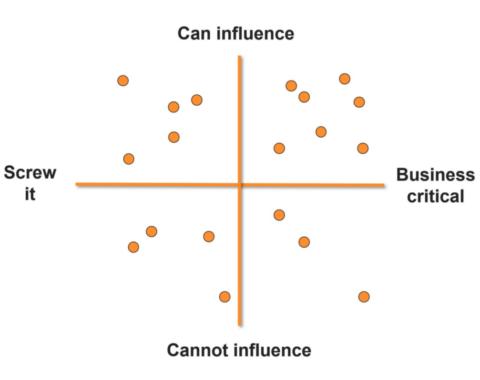

The second step is to work out a simple chart that maps the interactions along two axes. This is a highly subjective, but incredibly useful task, and, for once, a really useful workshop activity. This is what it looks like:

If you ask me, if you are not focusing on the stuff that is important to the business, and stuff that you can actually do something about, you are merely wasting your time and someone else’s money. But take my word for it, business leaders understand this chart and it is an incredibly effective tool for moving a project forward in a beneficial way.

The myth of “the user-experience team of one”

I come across far too many companies that tell me, “Meet Helen. She does our UX.” They think that because they’ve given someone a UX title that they are actually practicing UX. Alas, Helen probably spends most of her day trying in vain to get the resources needed to actually accomplish something, or is being asked to redesign graphic buttons and tweak some code.

Not surprisingly, the companies that hire a “Helen” (or “Rajay” or whomever) also complain that “We don’t really see the value of UX.” No surprise here.

Alternatively, I’ve also worked with companies that have UX teams of 5–10 people — none of whom have ever been allowed to talk to an actual user/customer/whatever! Most of these folks are pushing pixels, too, with little effect on the bottom line or influence on any customer-satisfaction surveys that come back. Again, the folks in charge usually claim UX has little value — “it’s just another buzzword.”

The truth is, you want a “UX team of EVERYONE.” I don’t think the folks who empty the trash bins in my hometown of Copenhagen, Denmark, sweep our streets, or wash graffiti off the walls think of themselves as part of the “UX team of Copenhagen.” But they are — and they very much influence the way in which our city is perceived by residents and visitors alike. It is incredibly important to take a very broad view of UX or you probably won’t see the benefits.

That said, a lot of talented people have figured out ways to game the system. There’s a really good book by Leah Buley called “The User Experience Team of One — a Research and Design Survival Guide” (Rosenfeld Media, 2013). Although I dislike the title (for the reasons mentioned above), Leah has incredibly valuable advice if you are working in a company that doesn’t yet “get what UX is all about.”

The great “UX vs. CX” debate

“Customer experience” (CX) is a big thing these days. After all, the customers are the ones who actually buy something and you can usually see the results in the sales figures. Hence, many so-called professionals claim that UX is a subset of Customer Experience. Or that UX is a subset of Service Design. This is not true, although both CX and SD are without question the most visible manifestations of UX design.

The CX people have got it right: A customer is someone who has had some kind of financial transaction with a company/brand/product. Think Apple.

The SD people have also got it right: In a world where “products” tend to look alike, the quality of service is often a key differentiator. Think airlines.

But UX is NOT, in fact, a subset of either CX or SD. For example, my cat is a “user” of the food I buy. I am the “customer” for the cat food. If the cat doesn’t like the food, I stop buying it. We are BOTH “users” of the product and the UX associated with it but in different ways. Similarly, many purchasing departments (“customers”) are not the people who will actually be using the products (“users”). Think medical disposables in a hospital.

Hence, while all “customers” are “users,” not all “users” are “customers.” These days, some folks are advocating for dropping the term “user” entirely and just referring to all this as “Experience Design.” I don’t really care one way or the other. But I personally find the word “user” extremely useful to describe the “thing” that is using whatever it is we are designing. Again, I urge you to take a broader view. Honestly, sometimes your smartphone is the “user” of a broadband network. This is an interaction that can be very relevant when working out the UX for an online service in an area with sketchy broadband coverage. People, devices, events. You need to look at all of these interactions.

“Jack-of-all-trades” is not a bad thing

A final note: The old expression “Jack of all Trades, Master of Nothing” suggests that being a “Jack” is somehow less valuable than a specialist. Or that a “Jack” has only slight knowledge of the individual subjects and isn’t worth listening to. I think both interpretations are faulty.

User experience turns this maxim on its head — really good UX designers understand a lot of subjects to a fairly sophisticated degree, including business models. And they usually demonstrate far more cultural literacy than most. Jacks-of-all-trades (sometimes called “T-shaped people”) are not dilettantes: They possess more than the rather cursory knowledge demonstrated by the average project coordinator. Alas, many of today’s UX practitioners promote their individual specialties (information architecture, graphic design, usability, content strategy, etc.) at the expense of others — often demonstrating a narrowmindedness that is downright counterproductive. No wonder the business community is so confounded and frustrated by the mixed messages coming from the many “experts” out here in cyberspace. On a side note, while I do believe that we are ALL designing UX, I’m not convinced any of us can truly call ourselves “UX designers” — specialties are good but an individual discipline should never become the main focus of any UX project.

Is UX dead? Hell, it ain’t even sick! I think it’s merely misunderstood and badly practiced.

Originally posted on the FatDUX.com blog.