In this post, I want to talk about why you’re not learning anything from your interviews. Over the last couple of months, I’ve heard several aspiring founders complain that they’d done some interviews but couldn’t draw any solid conclusions from them. Many of them figured that interviews simply couldn’t help them. So they chose to throw together a landing page instead: “Interviews are way too fuzzy, I need some numbers!”

But in my experience, a quality interview can be a real eye-opener. It can make you aware of what you thought was true but was actually just an assumption. You’ll probably be able to debunk some things fairly quickly, setting you on the right path (or at least taking you off the wrong one) before spending all your precious money on Facebook ads and LinkedIn campaigns. That said, interviewing is a skill and, if you ask the wrong questions, the data you get will be confusing at best. To help you, here’s a list of the mistakes I’ve witnessed most often and some tips on how to avoid them:

Mistake #1 You’re (mis)leading the conversation

If you talk about your product or service and the problem it should solve, that’s what the interview is going to be about. And that can create the illusion that what you’re working on is important to the person you’re interviewing – while in reality, it might not matter much to them at all.

How to avoid it

You can avoid this pitfall: first and foremost, ask your interviewee about their problems and challenges. Don’t just jump to your solution, see what they mention first! This will uncover what’s really at the forefront of their mind and is likely the biggest pain point they’re experiencing right now.

Asking someone what they did to address a certain problem is another good trick. Are they unable to name some specific actions they took? Then the problem probably wasn’t important enough to solve.

Example

Recently, I was doing interviews for one of my own projects: a tool to help founders analyse customer development interviews and discover Jobs to be Done. I started each interview by asking the founders about their background, the most recent interview they had done, and how they had gone about preparing and conducting it.

The founders talked about the challenges of convincingly presenting their findings to investors and stakeholders. They mentioned wanting tools that would help them create compelling visuals, too. But not once was analysing the interviews stated as the biggest problem. Or keeping track of what they’d heard. The founders simply jotted everything down in a small notebook and then decided on the next steps that way.

So I concluded my interviews by actively asking about data analysis. How had the founders gone about analysing their interviews? Had they experienced any difficulties? While some of them admitted that data analysis could be a bit challenging, it was obvious that this was a lot less important to them than the issues they had mentioned of their own volition. The energy with which they had expressed those concerns had been a lot greater.

At that point, I realised that it would be difficult trying to sell them a tool to help them analyse their interviews. After all, people are more likely to buy something they’re convinced they need.

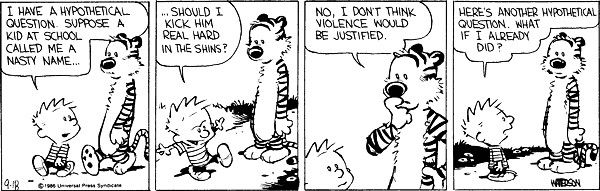

Mistake #2 You’re asking hypothetical questions

I know: it’s very easy to ask people questions beginning with “would you..?” I catch myself doing it sometimes, too. But people simply aren’t aware of what they would do in a hypothetical situation. They might know what they’d buy in a supermarket on a particular day, but that’s about it. So any answers you get to a hypothetical question should be taken with a (big) grain of salt.

How to avoid it

If, like me, you catch yourself asking one of these questions, make sure to ask a follow-up question about past behaviour. Because past behaviour is a much better predictor of future behaviour.

Past behaviour is a good predictor of future behaviour.

Even better: ask for an actual commitment! What better way to reveal what people would do than to prompt them to actually do it?

Example

Last year, I took part in a Startup Academy workshop organised by a friend of mine. It involved grouping people together and asking them to develop and test an idea for a new business in a weekend.

Armed with our pens and notebooks, we set out to talk to some strangers. We wanted to test the interest in our idea, a platform for Indonesian entrepreneurs to sell their local products in the European market as a way to support themselves in times of disaster.

We first tried asking people what they would do: “Would you buy this jar of spicy sauce made from local Indonesian entrepreneurs?” And, unsurprisingly, the answer we got was: “Eh, yes, sure!” We then followed up by asking for a commitment: “Ok, so do you want to buy it now for two euros?” Suddenly, we started getting answers like “well, I don’t have cash on me right now” or “we still have some spicy sauce at home so maybe another time.”

Everyone we approached followed this pattern. So who’s to say that anyone would have actually purchased the product had we offered it on an online platform? That experience taught me to be very wary of hypothetical questions as they often produce false positives.

Mistake #3 You’re forgetting the “why”

I’ve seen aspiring founders take interviewing to the extreme after learning about the MOM test and the Jobs to be Done interviewing technique. They ask their customers for details without reasons: where? when? with whom? etc. However, neglecting to ask why? means missing out on a key piece of the puzzle: the underlying needs that drive people to take certain actions. Additionally, facts-only interviews are often very boring, making it hard to keep the conversation going and to dig deeper.

How to avoid it

Simple: ask people about their motivations to do something. Basecamp’s Jason Fried wrote a very interesting article about this called The Why before the Why. It covers how understanding people’s motivation to shop before people’s motivation to buy helps to design products and services that sell.

Example

In my customer development workshops, I’ve seen many (practice) interviews fall flat after just five minutes. Tasked with asking an interviewee about their daily commute and how they’d got to work that morning, some interviewers asked for details like: “When did you leave? What did you take with you? How long did it take you to get to work? When did you arrive? Okay… eh, what else?”

That’s where the interviews often got stuck. The fact-checking questions failed to engage the interviewees, they didn’t elicit detailed accounts of the reasons behind their actions – which made it really hard for the interviewer to find something to latch onto and ask more follow-up questions about.

However, this changed when I advised the interviewers to ask a “why” question. Often, the conversations would immediately become much more fluent: “So, why did you take the car this morning?” “Well, it was raining, and the bus stop is quite far from my work. I had an important meeting and wanted to appear looking professional, not all soaked.” See, that’s the information you’re looking for! The “what” is often much more useful once you’ve uncovered the “why” behind it.

Mistake #4 You’re not going with the flow

If you’re going to follow a set list of questions that do not allow any diversions, you might as well distribute a survey. That would save you and the person you’re interviewing a lot of time. The great thing about talking to someone in real time is that you can dive deeper into interesting things that come up. You can uncover things that hadn’t even crossed your mind before.

How to avoid it

Use both techniques – but at different stages! Interviews are a great tool for exploration: delving into a topic and finding out what ideas people have. Asking a set list of questions (aka a survey), on the other hand, is much better for validation: confirming that what you believe is true for a larger group of people.

How I go about interviews is by following a semi-structured format. That means that I have a few topics in mind (and jotted down on a sheet) that I want to discuss as well as a few crucial questions I want to ask. But I allow ample time to dive deeper into topics that come up. My notes usually look something like this:

DNF = Do Not Forget!

My prep work enables me to ask questions like “really, how did that happen?” and “interesting, what did you do to address that challenge?” These spontaneous follow-up questions often help me to discover pain points that hadn’t occurred to me in advance.

But having some structure is good. My notes help me to remember all of the important topics and questions I wanted to ask. As a result, the data I collect in the interviews become comparable.

Example

Sometimes, your follow-up questions will cause the interviewee to digress. One time, I was asking someone about their news reading habits and the conversation ended up being about their honeymoon. So I gently nudged the conversation back to the topics on my list. Trust me, people will understand if you do this nicely. Just say something like: “How interesting, maybe you can tell me more about that another time? I would now like to ask you some more questions about that app you mentioned you use to read the news.”

Mistake #5 You’re focusing on irrelevant details

I’ve seen interviews with questions about all sorts of stuff. Interviewers try to capture everything because they believe they may uncover something of interest. But it is precisely this attempt to capture all sorts of details combined with an often limited timeframe that keeps them from getting to the good stuff! Aka what really drives people to use the products and services they use. And as stated in #4, insisting on too much structure leaves little room to explore and discover new things.

How to avoid it

Focus on factors that have a high chance of influencing product and service choices. Demographic details, for instance, can be important to ask about when you’re launching a marketing campaign. But they’re often irrelevant when you’re trying to build something people will use.

Example

A while ago, I was helping someone put together a service for renting expensive designer dresses for special occasions. She was very meticulous in doing her research. In fact, she had an entire Excel sheet with loads of details about every interviewee that she had filled out while conducting the interviews. And while she had gathered an incredible amount of information, she had no idea what was most important or what conclusions to draw.

Consequently, it was difficult to decide on the next steps. So I advised her to pick a few target groups she wanted to focus on first and to screen her participants accordingly. I also asked her to review the moments when these customers had bought or hired a designer dress for a special event. How had they gone about that – and why? By focusing on a few relevant questions, she was able to draw conclusions from her research. Instead of drowning in a bunch of information she couldn’t use.

Mistake #6 You’re talking to the wrong people

How many people should I interview? This is one of the questions I get asked quite often. In general, ten should be enough to detect some patterns – provided you’re talking to people from the same target group! If you interview people from wildly different groups, you’ll hear wildly different things.

How to avoid it

Make sure your target group is well-defined and based on relevant attributes. Try to determine the criteria that really influence whether people use your product or service. These might include certain demographics as well as things like having a family member with a particular pocket of knowledge or having been through a life-changing event recently. Select people who match your relevant criteria. Don’t get hung up on demographic details that could, possibly, have some influence.

Example

I’ve seen many corporate innovation teams end up doing 50 or more interviews because they couldn’t detect any patterns. One of these teams was developing a crowd-investing platform for real estate. When I asked what the target group was, they answered: “millennials looking to make more from their savings.” That includes a huge number of different people with widely varying goals, worries, and wishes. No wonder they had issues finding a common theme!

So I advised them to be way more specific. Perhaps even uncomfortably so. I wanted them to specify exactly where to go and exactly what to ask to identify their target group. And to segment based on aspects they knew had a big impact on the willingness to invest. In this particular case, previous interviews had uncovered that having a family member or friend who invested in real estate played a major role.

Practice makes perfect

Remember: interviewing is not rocket science. Anyone can conduct quality interviews! It just takes practice is all. So start with some mock interviews with your family and friends. Record the interviews, watch them a couple of times, and write down all of the things you want to improve.

I recommend picking topics you’re really excited about (and maybe have considered as a side project). For example, I practised my technique by asking people about the music they enjoy listening to and how they choose the ideal playlist for a house party.

Finally, always take a genuine interest in your (potential) customers. Put them at the centre of your interviews by focusing on their problems, worries, and wishes rather than your solution.