There are very good reasons to get out of the lab to do user research. For one thing, users don’t hang out in labs. To make it easy for people with time, transport, or mobility constraints to take part in research, we often meet them where they are.

For another, we stand to gain a lot from visiting people at home, work, and other places where they live their lives. This is where they do the things our products help them do. So these places are filled with useful evidence of what they really need.

As user researchers, it is our job to gather all this evidence. This is how we inform the design of products and services that work well for people. But just as importantly, we are here to give our teams direct exposure to users.

Making it possible for designers, product owners, developers, and other decision-makers to observe users firsthand is a very good reason to do research in the lab. The trouble is that the lab is just so different from real life.

- In real life, people often stop using a service when they reach an impasse. But in the lab, they trudge on.

- In real life, there’s no user researcher hanging about. But there certainly is in the lab.

- In real life, people get help or find novel ways to work around problems. In the lab, they tend to look to a moderator when things get tricky.

This post delves into each of these 3 ways that the lab is different from real life and how user researchers can work around these differences by inviting bits of real-life-like behavior into the lab.

1. In real life, people give up

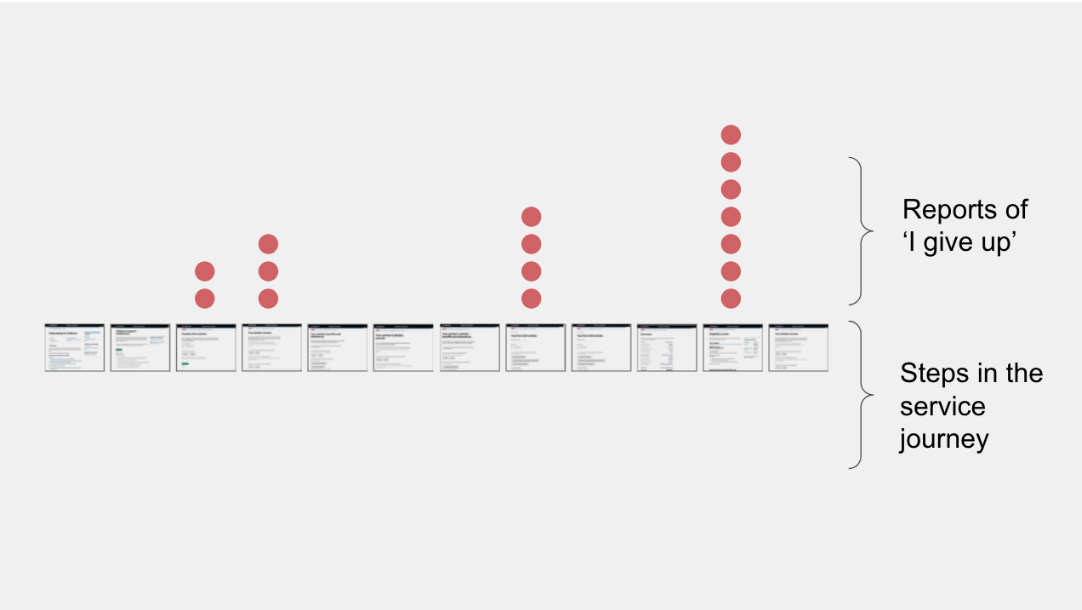

Once a service is live, our performance measurement tools show us points in a digital journey where people give up or stop using the service. If only we could know in advance where and why people quit, we could probably do something to preempt it. The trouble is that research participants don’t tend to say “I’ve had enough of this, I’m giving up” in the lab. Why not? Because they want to be helpful. They’ve reserved the time to be with us and removed the usual distractions. So they power through.

Make giving up an explicit option in the lab.

We can invite research participants to give up in the lab if they feel they would in real life. Tangible reminders can help them feel comfortable about exercising this option like this easy-to-assemble ‘give up’ flag. Hand it to the participant and ask them to raise the flag whenever they feel that in real life, they’d probably drop this and get on with something else.

A ‘give up’ flag helps to remind participants that they don’t need to power through.

I used this on a government service that required users to input a lot of information (but also brought them life-changing benefits.) Some participants waved it, others simply mentioned when they got to a point where they would probably give up. For them, the flag functioned as a visual reminder that giving up was an option.

Each time a participant gave up (by waving the flag or simply saying ‘I’d probably stop here’), I recorded at which point in the journey and why. I then charted these likely drop-off points and reasons for them to make them visible to my team. Together, we discussed what changes might help and prototyped helpful alternatives. After testing them again, we found reports of likely drop-off decreased or disappeared.

Each time a participant waves the flag, record the point in the journey as well as the reason for giving up.

2. In real life, people don’t have an expert looking over their shoulder

Another thing that makes the lab different from real life is the presence of a researcher. Observer effects include all sorts of behavior that wouldn’t happen in real life. One of the most noticeable is when participants turn to us for a steer.

Because we structure research sessions and know a thing or two about how a product works, participants may view us as authorities. No matter how neutral we claim to be! Having a supposed expert in the room makes it very tempting for them to ask us whether they’re on the right track and what to do next. As decent human beings, we may be tempted to help them out.

Of course, once we answer their questions explicitly or give even subtle cues of how things work, we’re no longer really observing people interact with the service. We’re observing them interact with the service plus us. And the trouble with that, of course, is that we won’t be there in real life.

Avoid steering participants in a particular direction.

So how can we be decent human beings and decent researchers when participants ask us “Is this right?” or “How does this work?”. We can take inspiration from Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead:

In question tennis, players must answer questions with other questions. Because we’re naturally curious and inquisitive, we often have questions about participants’ questions. “What makes you ask?” or “What do you think this might mean?”, for example.

Alternatively, to put participants who look to us for feedback at ease without steering them, we can thank them for expressing their doubts and remind them how useful it is for us to learn where things aren’t clear. As ever, emphasize that you’re not evaluating how they perform with the service, but how the service performs for them!

3. In real life, people find help

Another consequence of a user researcher’s presence in the lab is that participants don’t seek help in the way that they might in real life. But teams need to understand whether people can find the support they need to succeed with the service.

Leave the room.

One way we can observe how people might look for support in real life is by leaving the room. We excuse ourselves for a period, make internet connections, computers, and a phone available for participants to use, and invite them to find help when they may need it.

With the participants’ permission, we record what they do:

- What words they use to search for answers

- Which pages or tools they access

- Who they contact

This lets us evaluate how easy or difficult it is to find help, what terms people use to describe what they need, and what tools or support channels they choose.

I hope this helps you use the lab as a gathering place for users, idea generators, and decision-makers as well as a place to observe things you need to observe but that wouldn’t ordinarily come up in the lab.